What does film art contribute to the ARCHAEOLOGY OF VISUAL EXPERIENCE?

What does film art contribute to the ARCHAEOLOGY OF VISUAL EXPERIENCE?

What does film art, which is young, contribute to the ARCHAEOLOGY OF VISUAL EXPERIENCE? / This art can’t dig / It hungers for experience / The film camera and new tools of digitality / “Reading like the wise men in Babylon once did in sheep’s liver… “

In the hothouses of “light-play,” cinema, cameras, and pioneering spirit…

… What can the last offspring of the arts, film (before graffiti), do that other arts cannot …

The subject of film is the moment, the lightning-like trace of detail. What we filmmakers (and the audience) do not perceive—due to our habitual vision, the structure of our imagination, and its filters—appears. The camera is incorruptible as an observer. Filmic effect is based on “astonishment.”

Montage creates relationality. Times that are strange to each other come together in film. It’s never about a picture. Always about the difference, the polyphony, the relationship linking countless images. In this respect, film corrects the “moment.” It is never mere present but is interested in all grammatical tenses - and the ungrammatical ones too. In this respect, film entails a correction of everyday perspective.

The film image develops counter-images to keep the images relevant. In this, that which is topical is no better than that which is imaginary, the imaginary is no more important than the observable. The film image is anti-hierarchical. The film image always involves two image streams: the subjective stream in the viewer and the quasi-objective stream on the screen. The screen is just a pretext for viewers to look at their own pictures, which they have long possessed.

The principle of film is externally montage. In substance the filmic principle is constellation. Montage technique does not “use” or “undo” a previously seen image, but rather reinforces and renews it. Supplemented by the subjectivity of the viewer. Montage combines image fragments in which seven, seventeen, or eighty-six images enter into dialogue with each another.

Film cameras and the tools that serve as virtual tools are obsessed with details. They see something that the filmmaker discovers only at the editing table. This, the more decisive precision of perception - which counters the habitual gaze - is what Walter Benjamin calls the optical unconscious of the film camera.

A magical agent of cinema, the inner basis of the “dream factory,” was a slowing down, a temporal delay. In the classic projection apparatus and the classic camera, a 48th of a second was required to transport the negative or copy, and only a 48th of a second was available for the exposure. In this respect, darkness prevails for half the time of a classic cinema screening. During this pause, which consciousness does not perceive, the brain synapses and all human sensuality are at their highest level of activity. FINALLY THEY ACT AUTONOMOUSLY AND SELF-REGULATE IN PUBLIC!

They demonstrate thankfulness for this with imagination, with associations, with something irreproducible and unpaid for in the audience. This something has accompanied all classic films.

- This - a happy coincidence of technical evolution - was lost in the digital age and can be repeated to only a limited extent and in completely new ways. Nowhere do we have DARKNESS IN THE MIDDLE OF LIGHT. This is about the pause that adapts all the times of the world and forms of liveness to the slow beat and tonal key of liveness. The filmic principle can be described as the SEARCH IN THE GAP OF ALL SPEEDS OF THE PRESENT FOR A PAUSE THAT BRINGS THE IMAGINATION, THE SENSES, AND UNDERSTANDING INTO RELATIONSHIP. ONLY IN THIS PAUSE DO THEY CONNECT WITH EACH OTHER.

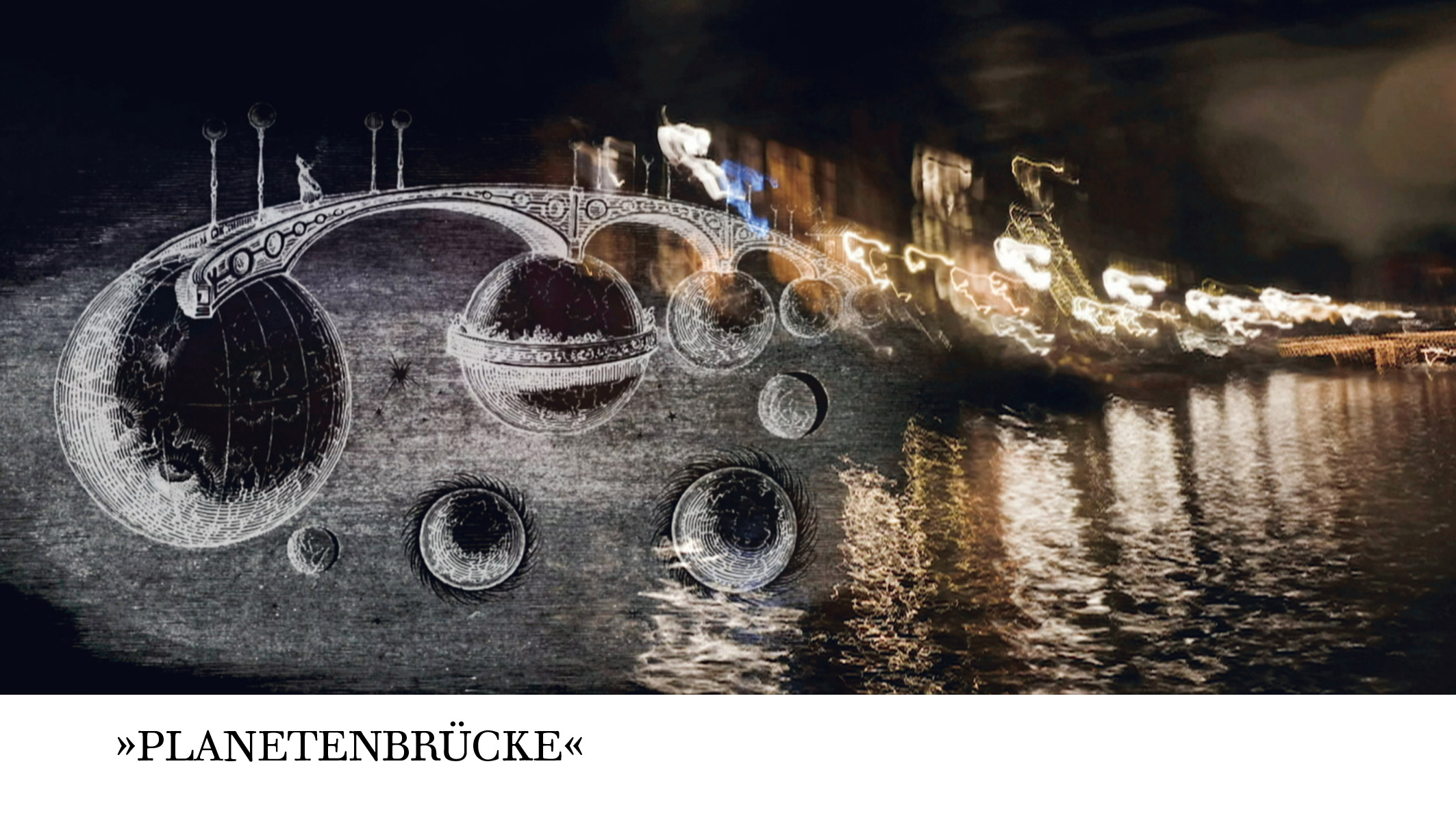

This image comments on the final image of the first volume of Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project: Grandville’s Planetary Bridge from 1820. Here with “Lights in the Harbor” from the Separatrix book project by Katharina Grosse and Alexander Kluge (pages 438-439, chapter 8, camera images taken in 48ths of a second).

A Weather of Light

In this instance, my cameraman Thomas Willke filmed in the harbor of Amsterdam at night using this method. The waters in constant movement, the lights of the harbor and houses, show the autonomous movement, the swirl of light in the still images, onto which images can then be placed when the film is shot again. All of these are artifacts, “concentrated coincidence.” For film and literature, neither of which can paint, this is an authentic form of expression.

SUN OVER THE WATERWAYS OF THE LIDO

The Cinema in the Head of the Spectator

A smell of mud and fish protein mixed with salt water. From the Adriatic coast opposite a strong breeze. If you go in the shade from the Film Festival Palace past the fashion boutiques, you get to the Palace Hotel Excelsior. I am sitting on the terrace of this grand hotel opposite the Nobel Prize winner Professor Eric Kandel. He seems ageless. On the one hand he belongs to the generation born in 1929 (the Venice Film Festival was not founded until 1932); on the other hand, a piece of his soul seems to have been stuck at the age of nine. He sits there with the curiosity of a nine-year-old, but also full of memories. He calls himself a cinema addict. This explains why he goes to film festivals on holiday. He is the editor of the seminal work on neurology and brain research used in medical schools in the USA.

Professor, you say that the groups of brain cells that “spark” every

second, as if in a concert, speak a language that we do not understand

and that we also cannot speak. And this language of brain cells and

networks has nothing to do with anything that exists outside the human

head.

If you measure, you measure “expressions.” In the length of a fraction

of a second. You can imagine this elementary communication as a syllable

or as very short bursts of birdsong. An absolutely “meaningless text,”

if you look at such a recording. It is, however, never isolated, and

also not like a “concert,” as you suggest, but rather like a score or,

better still, like the whole history of opera as a score.

And between this autonomous brain activity, these clearly very fast

occurrences, and the environment, nothing but misunderstandings?

Which in the course of evolution have tuned into one another. Only

those misunderstandings that fit together remained, so that the brain

(even if it does it with a fallacious text) reproduces the outside world

so to speak against its will.

So, are the inside and the outside opposing texts?

That is exactly what I am saying. It was for this discovery that I got

my Nobel Prize.

And how do the impressions in the cinema relate to that? They have only

been part of the evolutionary process for 120 years.

For a forty-eighth of a second it is dark and for a forty-eighth of a

second there is an image. This is an interesting kind of movement for

the brain.

What does the brain “see” of this? Does it see that black between the

images, the transport phase? Does it react independently to the moment

in the transport phase when it is dark in the cinema for a forty-eighth

of a second, i.e., with signs that it creates itself and only

understands itself?

Similarly.

Like in a dream?

Or under the influence of drugs. It “sees” the black continuously,

whereas the same brain sees the “image” as continuous, even if it is

also “flickering.” A polyphonic impression.

Unconscious?

Nonconscious. I know, of course, that I am sitting in a movie theater.

Or rather doubly conscious: I see TWO FILMS, one made by the brain

itself out of darkness, and one in light and color, as reported by the

eyes, but with a collective impression already created by our ancestors,

as triggered by the content of photographic images.

The stimulant that causes the brain to dream is the rapid exchange?

Which, however, in the case of a two-hour film produces a whole hour of

darkness (the brain works autonomously) and a whole hour of images (the

brain responds to stimulation).

And that is better than reality?

Much better.

The Nobel Prize winner had developed his primary research by studying the nervous system of a sea snail about the size of a rabbit. Such an animal, intelligent in its own way, with its large but not especially numerous nerves, would not, he said, be able to make anything of the kind of twin-streamed information one encounters in the cinema. Only the human head was (since the stone age in fact) set up as a movie theater. The invention of cinemas had, in this sense, led to a kind of “recognition.” Something that groups of brain cells had always been trying out suddenly appeared as a possible experience. This constituted the wonder of cinema. He, personally, Eric Kandel claimed, considered the pleasure of cinema–which he exposed himself to from time to time–no less valuable than his scientific activities, which, however, earn him his living.

- The Exhibition in the Uffizi in Florence

- What does film art contribute to the ARCHAEOLOGY OF VISUAL EXPERIENCE?

- The Time Total, an Achievement from the Treasure Trove of Film Art, as Not Just a Technical Principle, but as a Content-Related Principle