The Exhibition in the Uffizi in Florence

The Exhibition in the Uffizi in Florence

We today are dwarfs on the shoulders of giants. I felt this strongly at an exhibition by the Fundaziun Nairs in Switzerland. The title of the foundation’s three-day event in 2022 was: “Colloquium Warburg’s Passage.”

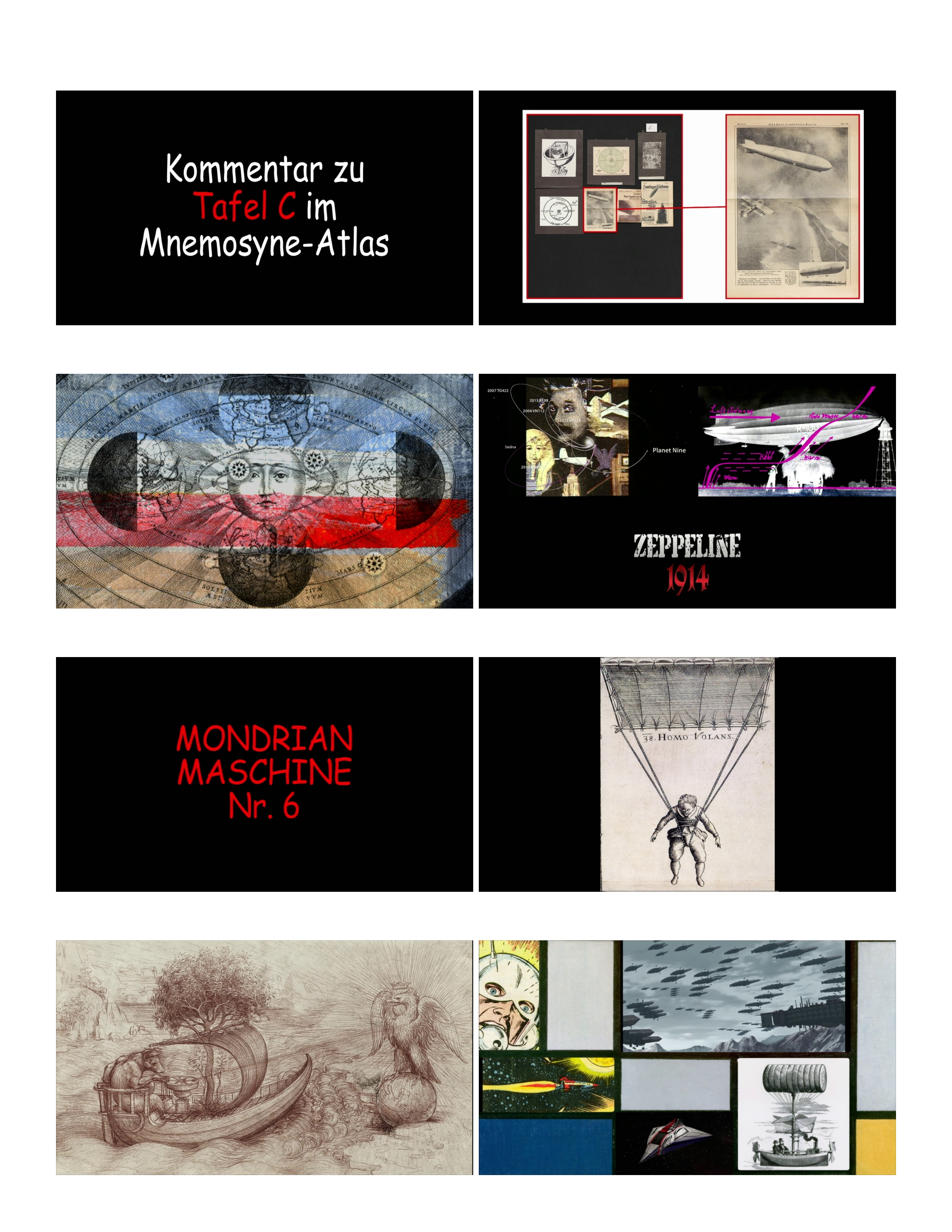

For this exhibition I created commentaries in the form of panels (prints on aluminum, wood, and other materials) and films.

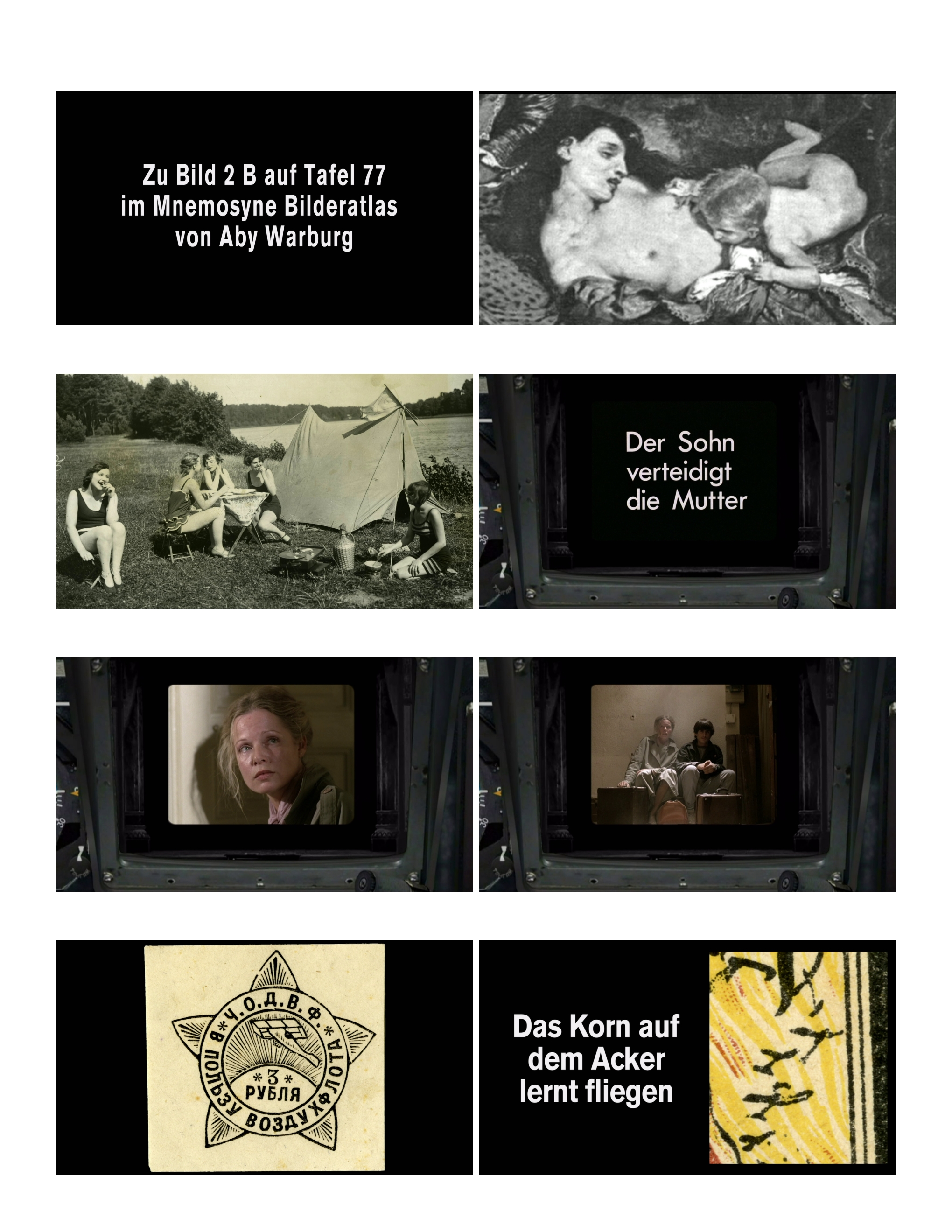

Screen 1: Commentary on Panel C / Mondrian Machine No. 6: The Flying Human Being Screen 2: Commentary on an image from plate 77 of the picture atlas: “The son defends the mother”

Following the exhibition at Fundaziun Nairs, Prof. Dr. Gerhard Wolf from the Max-Planck-Institute in Florence curated an expanded exhibition of my commentaries in the Niobe Room of the Uffizi Galleries.

Here, out of courtesy to the place and the images already there, the following was added:

Screen 3: Digital commentary on “The Triumphal Entry of Henry IV into Paris” by Peter Paul Rubens / “The Unequal Eyes” / Death of the Good King Henry IV in May 1610. The music ranges from John Cage’s “As Slow as Possible” to György Ligeti’s “Lontano.”

As mentioned above, panels made of aluminum and wood accompanied the screens in Switzerland and Florence. They also showed pictures from the book that Katharina Grosse and I co-authored, The Separatrix Project. This book is inspired by the philosophy of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and his theory of “seams between irreconcilable opposites.” It is not the center that determines the essence of a thing, but rather the outer skin, the “contact with the outside.” This is the diametric opposite of Cartesian dualism. Katharina Grosse’s watercolors in the Separatrix Project book also correspond with images from the Mnemosyne picture atlas.

In the meantime I have continued working. One important reason for this was that I wanted to respond to the Cornell University Library collection pertaining to Aby Warburg’s atlas of images. However, I am generally convinced that we today would do well to continue solitary (“gem-like”) approaches to work such as those used by Aby Warburg and Walter Benjamin. The fact that we are dwarfs doesn’t keep us from working. We will not be able to respond to the madness in our century - which astonishes me - if we do not call on all allied, emancipatory, constellative, generous-minded spirits and continue their work. Modernity is not a question of mere innovation, but of careful collection and repair work.

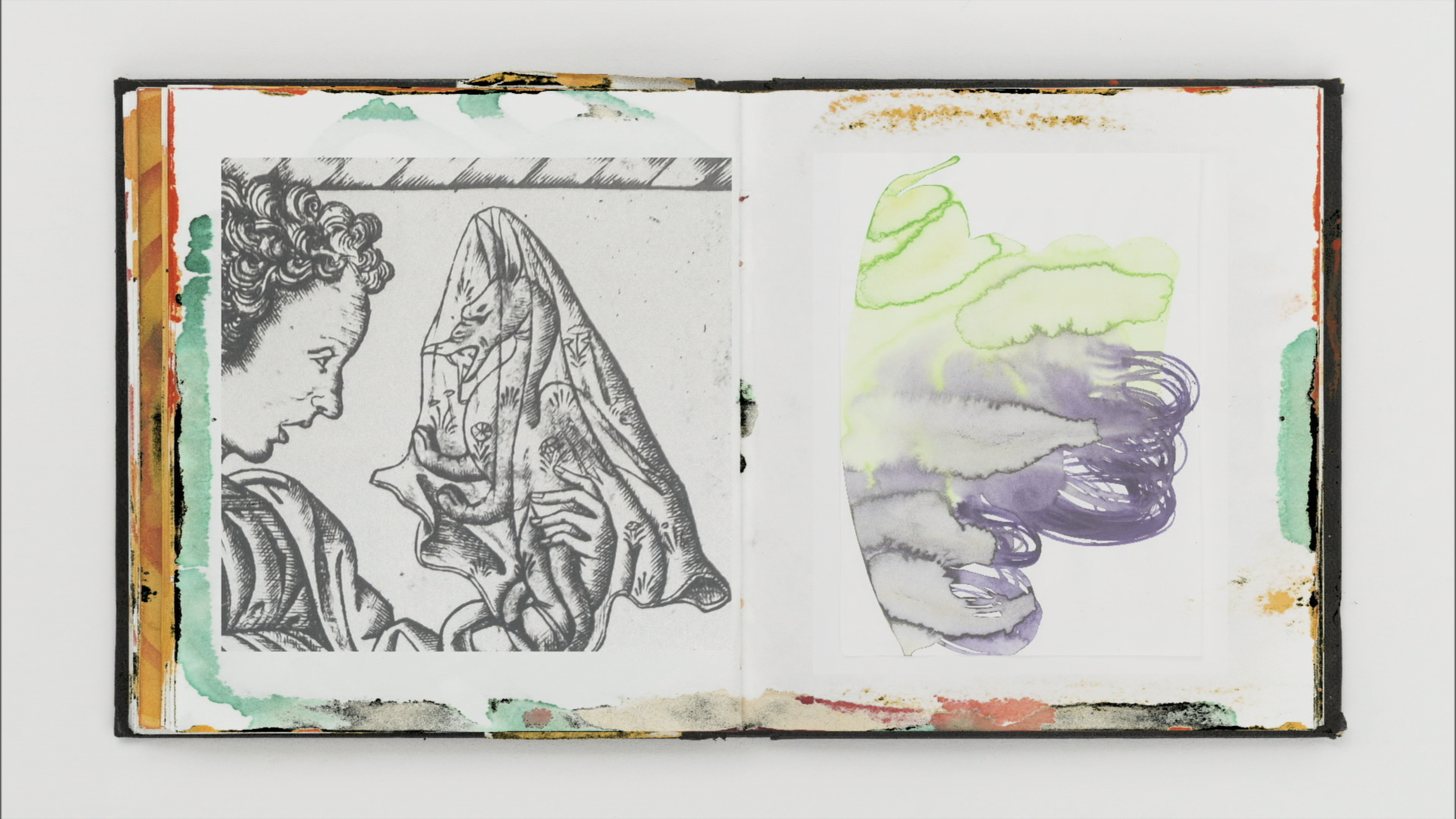

Taken from the picture atlas, the image on the left has been enlarged. The painting from the early Renaissance is entitled “Logica.” The “snake” or “biting monster” is covered by a cloth. The image conjures associations with “Eve and the serpent,” and it is likewise striking that “logic as an animal” appears to be obviously aggressive and biting. The limbs have claws. The “firm grip” is repeated in the young woman’s hand. On the right in the picture we see a watercolor by Katharina Grosse (Katharina Grosse and Alexander Kluge, The Separatrix Project, Spector Books, 2022, 584-585).

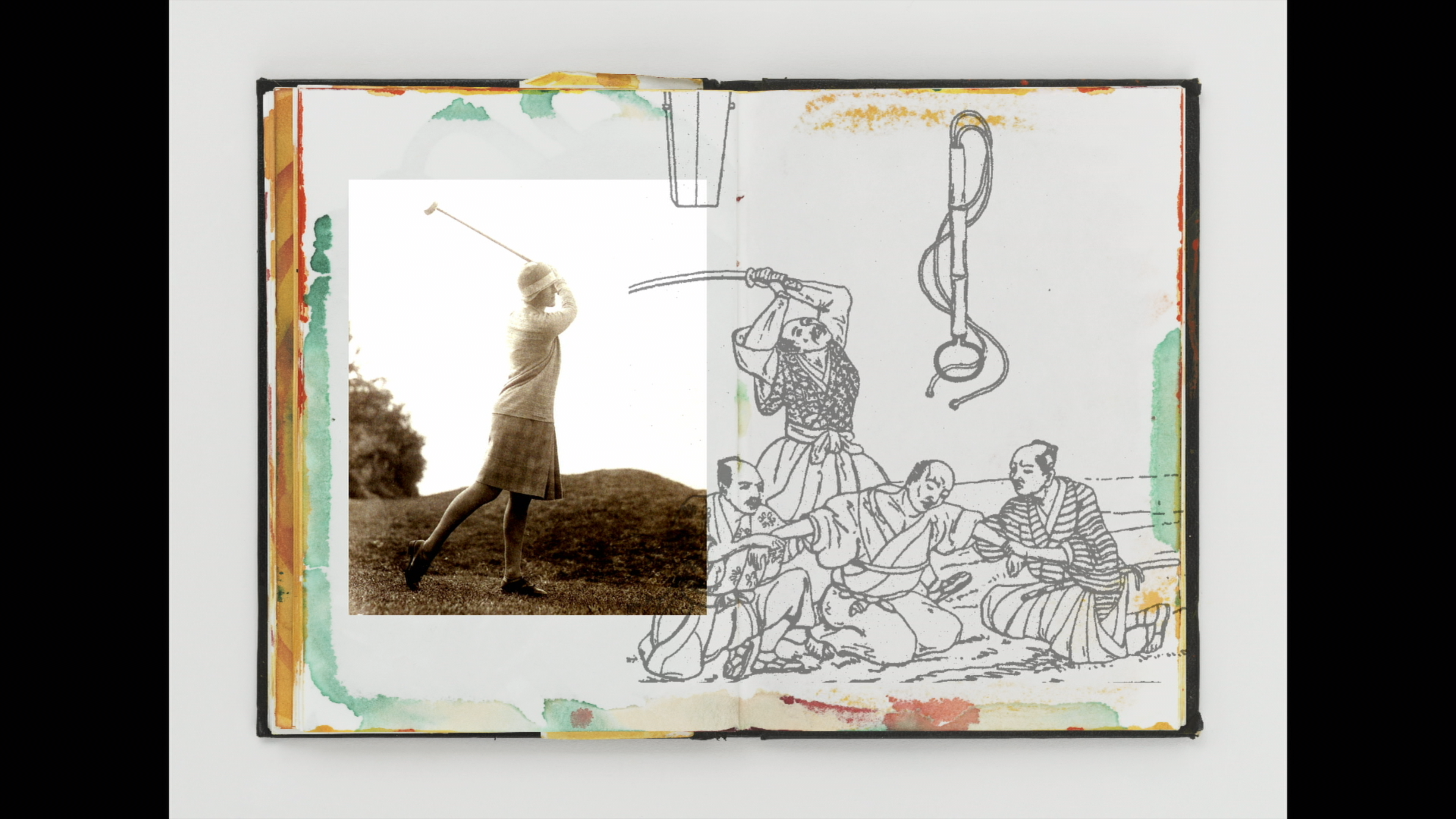

The image on the left from Panel 77 shows the golf champion Erika Sellschopp. The gesture in which this “athlete,” ninfa, and goddess of death holds the golf club is also the gesture with which - in another place in the picture atlas - the companion of a samurai cuts off the head of his master, who has just committed seppuku, to shorten the torment of the beloved Lord. But this is also the striking direction used by every skilled executioner who kills with the sword.

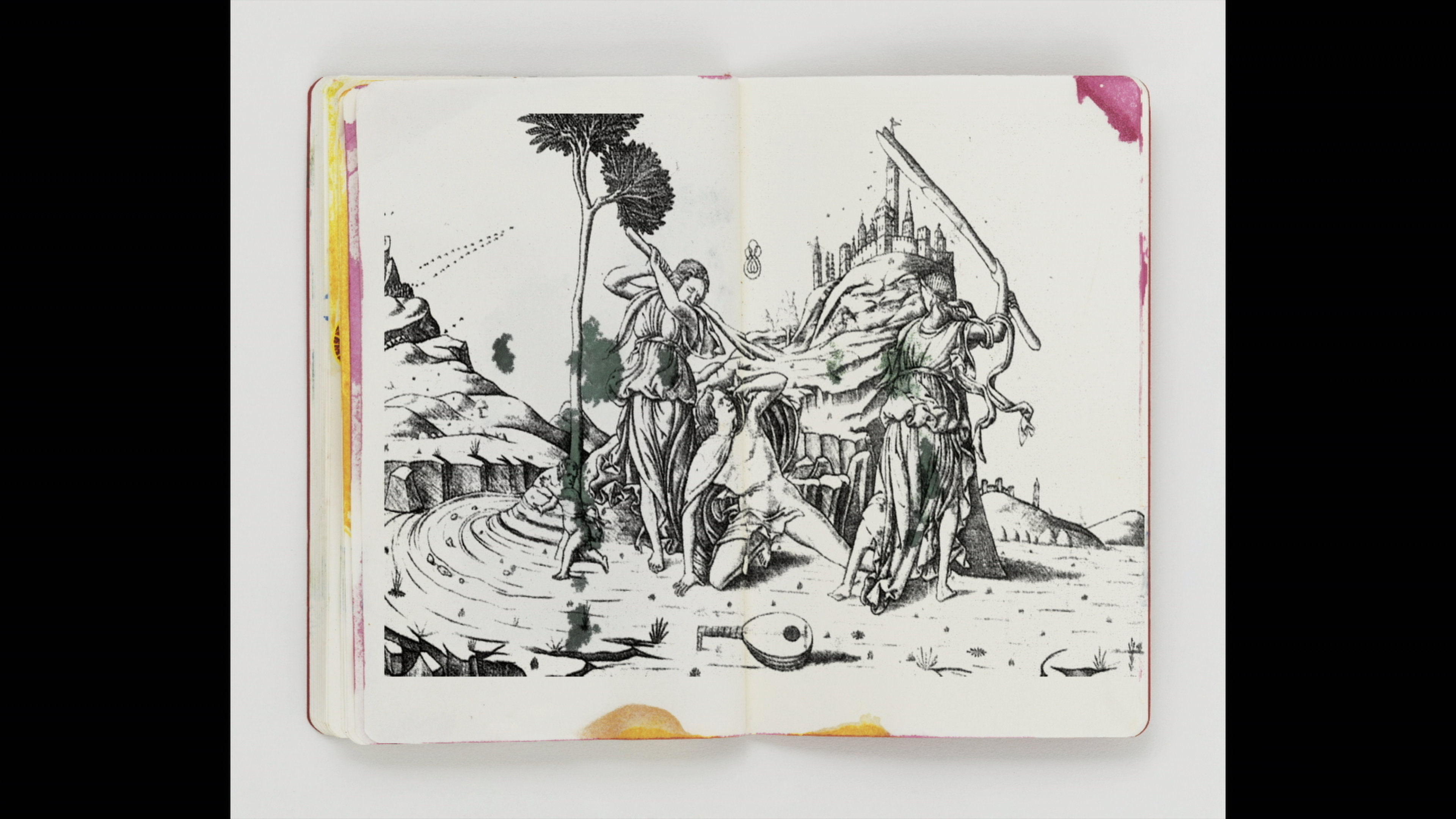

Death of Orpheus

We encounter the same striking gesture on another panel from the picture atlas: Death of Orpheus. Tessanian women who belong to a cult of Dionysus kill the poet - according to Ovid. In the end, separated from the body, the head floats down the stream towards the sea. This head still sings. It will land on a blissful island in the Aegean.

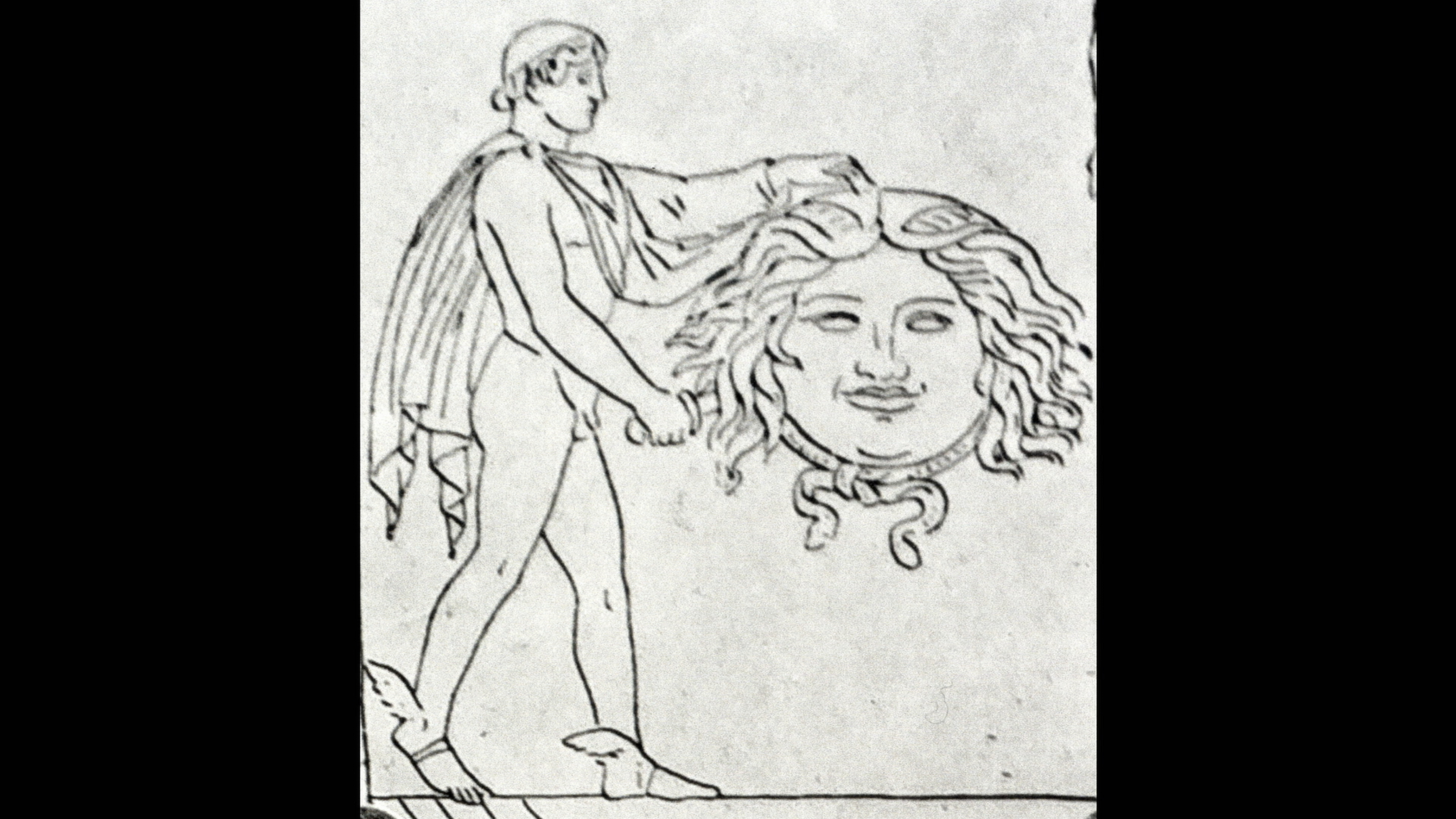

Another constellation of the same motif: In an Arabic variation. Perseus (“as a star image”) cuts off the head of the demon Gul.

Perseus with the head of Medusa.

Contact Sheet for the Exhibition “Colloquium Warburg’s Passage” in the Fundaziun Nairs

On Panel 20 – Perseus with the Head of the Demon Gul (as a Star Image)

Apparently Aby Warburg is struck by the fact that the story of Perseus, who cuts off the head of the terrible ghost Medusa, is a traveling story. According to Warburg, it comes from the Orient. But it also migrated from the Greek story back to the Orient. In the picture, a hero beheads the demon Gul by cutting off his head.

One of the basic assumptions in Dialectic of Enlightenment by Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno, a text to which I adhere, is that one cannot escape the demonic, the ghosts, the giganticness of the non-human, or the monstrosity of the past by beheading them. According to Max Horkheimer, Theodor W. Adorno, and also my belief, nothing is ever decided by cutting off the head. It is also - and here I am following Aby Warburg’s way of thinking - by no means certain that the demon or the “indomitable” or the “abyssal in nature” or “the malicious tunnels in the human soul” - all of these are spirits, spiritual beings – could even be beheaded at all. They are just released into the world in a free-floating state, and over time they add up to a kind of “demonic weather front.”

The Arabic version of the image from Abd al-Rahmann’s The Book of Fixed Stars on Panel 20 made a strong impression on me. In Aby Warburg’s work one can find numerous versions of this violent encounter between Perseus and Medusa. It is important to me that in ancient mythology the emergence of POETIC POWER, symbolized in the heraldic animal of poetry, Pegasus, is focused on this STRIKE INTO MEDUSA’S NECK. Because the birth of Pegasus derives from the drops of blood and bone splinters directly after the blow that separates Medusa’s head from her spine. Poetics comes—according to Ovid and Adorno—from such a deed and such bitterness. Poetics does not come from beauty and certainly not from entertainment. Neither does poetics come—unfortunately—from freedom and desire alone. Poetics arises out of confrontation with bitter suffering, such as that which characterizes the guillotine in the fifth year of the great French Revolution and the Mauser in the Russia of 1937, which kills proven revolutionaries.

The challenge posed by Aby Warburg’s constellations is this: If all great art is grounded in bitterness and suffering, how can I nonetheless generate enough desire and freedom subcutaneously—under the skin—to create effective storytelling against bitter fate? “The power of the factual,” that is the enemy of imagination. Imaginative capacity possesses a natural energy. Engaging it in a constellative way is a vital aspect of Warburg’s approach to his “atlas of images.”

- My Motive

- The Exhibition in the Uffizi in Florence

- What does film art contribute to the ARCHAEOLOGY OF VISUAL EXPERIENCE?